Soundblaster X-Fi XtremeMusic | HotHardware

When someone talks about ways to enhance your gaming experience, we typically focus on faster graphics cards and high resolution monitors. Over the years, this has typically been the only way to dramatically enhance the way games were played. However, with the launch of Doom3 roughly a year ago, the gaming world soon realized that there was much more than graphics in an ideal gaming experience. For the first time, developers focused a significant amount of attention towards the sound effects in the game. The end result was a title whose sounds were as dramatic and intense as its graphics. Gamers were hooked and were anxious to have this new level of realism in all their games.

Although the main reason many of us buy the latest and greatest hardware is to have a better overall gaming experience, we also have some other uses for our systems that help us justify the hardware costs. From music collections to DVD libraries, most PC’s these days are a personal multimedia theater. A focus on better audio hardware can have a profound effect on how songs will sound and DVD’s will be watched. Subtle tones in songs can now be heard and special effects in movies can be much more pronounced and enveloping. Provided you’re using high quality speakers, an upgrade to a new sound card can do wonders for nearly every aspect of your daily PC use.

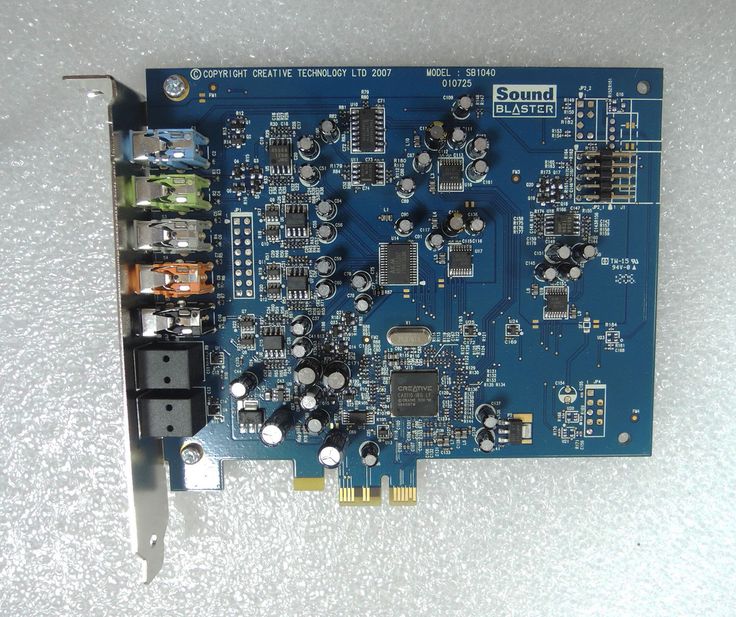

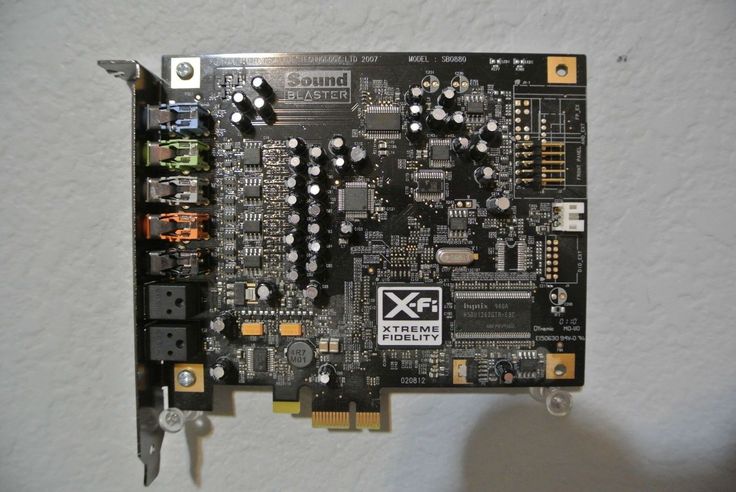

Creative Labs has always been a leader in consumer sound cards with their hugely successful Soundblaster products. From the original Soundblaster through the Audigy2 family, Creative has done a fair job of adding new features and functionality to each new product launch. In keeping with tradition, Creative Labs has done the same with the launch of the new Soundblaster X-Fi XtremeMusic. However, with this launch they attempted to go one step further beyond new features and functionality and add higher performance to the mix. With up to 64MB of on-board memory (X-Ram) and a ton of gaming-specific features, Creative claims that this new family of sound cards can actually give gamers a higher average framerate than when using their traditional integrated audio solutions. With such a robust set of features and claims, we were more than a bit anxious to get one of these cards installed and witness its performance first-hand.

With such a robust set of features and claims, we were more than a bit anxious to get one of these cards installed and witness its performance first-hand.

|

|

24-Bit 7.1 PCI Audio Accelerator |

|

|

Technical Specifications |

Product Highlights |

| Input/Output •Full duplex •Maximum Recording Depth: 24 bit •Maximum Recording Rate: 96 kHz •Maximum Playback Depth: 24 bit •Maximum Playback Rate: 192 kHz •Amplified 2.  0 V RMS output 0 V RMS outputAudio Quality (All Channels) •Frequency Response: 10Hz to 24kHz, <+/- 0.15dB •Signal to Noise Ratio: 109 dB, A-weighted (Typical) •Total Harmonic Distortion: 0.004% (Typical) Quality Connectivity Features Standards Compatibility |

DSP Algorithms •X-Fi 24-bit Crystalizer™ enhances MP3s and movies •X-Fi CMSS-3D allows you to upgrade your MP3 music and movies into surround sound •SuperRip™ allows you to rip your CDs into Xtreme Fidelity quality •EAX ADVANCED HD™ 5.0 delivers incredibly realistic gaming audio Entertainment Mode (R) Digital EX decoding! Gaming Mode Audio Creation Mode (R) sampling, and 3DMIDI for amazing flexibility and recording results.

|

NR603 SB0460 | Creative Sound Blaster X-Fi Xtreme Music

|

|

The five scariest musical instruments ♫ IMI.Journal

We wrote about what makes horror music scary, now we tell you how it is created.

Theremin

What it is

A unique instrument that can be played without touching, invented in 1920 by Soviet electrical engineer and musician Lev Theremin. nine0009

Two antennas emerge from the wooden case of the theremin, one controls the volume of the sound, the other controls its pitch. Bringing your hand closer to a vertical antenna increases the pitch, and moving your hand closer to a horizontal antenna decreases the volume.

Theremin was conceived to perform classical music and even as a substitute for an entire orchestra, but these plans did not materialize. Nevertheless, at the turn of the 1940s, American big bands began to use the instrument at concerts and in recordings, and in the 1960s and 19In the 70s it was played by psychedelic bands Lothar and the Hand People (USA), The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band (UK) and even Led Zeppelin (in the song «Whole Lotta Love»), among others.

How it sounds

Due to the lack of physical contact between the musician and the theremin, melodic playing of the instrument requires special skills and increased attention to hand movements. However, improvisation on the theremin allows you to achieve a strange and mysterious sound. The invention of Lev Theremin is perhaps best suited for creating howling sounds that evoke associations with both a gust of wind and something paranormal. nine0009

Where to hear it

In the movies, the lingering and ominous sounds of the theremin began to be used to sound UFOs and other anomalous phenomena in the 1950s. So, the instrument can be heard in the classic sci-fi films The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), It Came from Outer Space (1953) and Forbidden Planet (1956).

Waves of Martenot (Ondes Martenot)

Waterphone (Waterphone)

What it is

A musical instrument invented by American artist Richard Waters in 1968-1969. The waterphone consists of a stainless steel resonator bowl (which can be filled with water — hence the name) and bronze rods of various lengths and diameters.

You can play the waterphone with a bow, sticks, tap on it with your fingers, and so on — it depends on your imagination. The amount of water in the resonator bowl of the instrument allows you to adjust its sound, thereby achieving a variety of effects. nine0009

The amount of water in the resonator bowl of the instrument allows you to adjust its sound, thereby achieving a variety of effects. nine0009

What it sounds like

Depending on how you play it, the instrument can produce soft, ambient sounds, as well as harsh industrial grinding sounds.

Where to hear it

Since the late 1970s, the waterphone has been used in voiceovers for horror and science fiction, from Star Trek (1979) and Poltergeist (1982) to Aliens (1986) and The Matrix ( 1999).

Blaster Beam

What it is

Created in the early 1970s by American artist John Lazell, a stringed electric instrument with a long metal body (from 3. 5 to 5.5 meters) on which strings with magnetic pickups are strung like on an electric guitar. You can play the blaster beam both with your fingers and with any means at hand.

5 to 5.5 meters) on which strings with magnetic pickups are strung like on an electric guitar. You can play the blaster beam both with your fingers and with any means at hand.

What it sounds like

The rich spectrum of deep and atmospheric sounds of the blaster beam evokes something creepy and gigantic — for example, with the inhabitants of the water depths or the movement of stars and planets. nine0009

Where to hear it

Although the blaster beam was created by John Lazell, the instrument was popularized by musician Craig Huxley, who received a patent for an unusual device in the 1970s. For the first time, his «cosmic» sound was heard by a mass audience in the first «Star Trek» (1979), the soundtrack to which was written by Jerry Goldsmith. With the help of a blaster beam, the filmmakers voiced V’Ger, a mysterious life form of colossal proportions that threatened to destroy the Earth.

In addition, the blaster beam sounds in science fiction films and horror films Pitch Black (1979), Forbidden World (1982), Escape from Sleep (1984), Cloverfield 10 (2016) and others.

Apprehension Engine (Apprehension Engine)

What it is

Unlike the other tools on our list, the Apprehension Engine was designed specifically for horror film dubbing. In 2016, the instrument was designed by Canadian composer Mark Corven, the author of music for the horror films Cube (1997), The Witch (2015) and guitar luthier Tony Duggan-Smith.

According to Korven, the monotonous and plastic sound of soundtracks to most modern horror films prompted him to create a fear machine.

The Spooky instrument consists of a sounded wooden body to which twisted metal rulers, springs and other materials are screwed.

How it sounds

When you listen to the fear machine, you understand that the sound of the instrument does not need any processing. Metal squeaks, rattles, rustles and other sounds of the “horror device” already give you goosebumps. nine0009

Where to hear it

The instrument can be heard in Robert Eggers’ films The Lighthouse (2019) and The Witch (2015). Instructions for assembling the «generator of evil» are posted in the public domain.

How does music convey and evoke emotions? An excerpt from the book of an English scientist

Music is one of the most impressive phenomena in the world. It can give you some thoughts, make you cry and laugh, mentally return to distant memories, give strength, even fall in love. But why and how does it work? Is there any rational explanation for this, or will this sphere of art remain enveloped in a mystical veil? nine0170

With all this, the English scientist and journalist Philip Ball tries to understand his book «Musical instinct. Why we love music» , which was published by Bombora publishing house. He starts with the simplest things, that music is sound waves, tells how they interact with the human body and how they affect it. Then he begins to go deeper and deeper into what compositions consist of, understands what notes are, how songs are recorded, and, most interestingly, tries to find the answer to the question — how composers choose which note to write. This question seems a little ridiculous, but by asking such an absurdity, Ball gets to a more difficult dilemma: why does music make us feel certain emotions. nine0170

Why we love music» , which was published by Bombora publishing house. He starts with the simplest things, that music is sound waves, tells how they interact with the human body and how they affect it. Then he begins to go deeper and deeper into what compositions consist of, understands what notes are, how songs are recorded, and, most interestingly, tries to find the answer to the question — how composers choose which note to write. This question seems a little ridiculous, but by asking such an absurdity, Ball gets to a more difficult dilemma: why does music make us feel certain emotions. nine0170

© Bombora Publishing House

Do you know this?

«Suddenly (I) experienced an incredibly strong sensation both in my body and in my head. I seemed to be seized by a colossal tension, similar to severe intoxication. I felt delight, undisguised enthusiasm and was completely absorbed in the moment. The music seemed to arise from I felt the spirit of Bach permeate me: suddenly the music became so obvious. »

»

Or is it?

«I began to realize that the music was taking control of my body. I felt some kind of charge … I was filled with a huge wave of warmth and heat. I greedily grabbed every sound … I was captured by every instrument, I took everything that he could to offer me … Everything else ceased to exist. I danced, twirled, surrendered to music and rhythm, I was in seventh heaven and laughed joyfully. Tears appeared in my eyes — no matter how strange it seemed — and with them came liberation. » nine0170

If music has never made you feel that way, now you most likely feel like the party has passed you by while you were bored in the corner. Well, except for the alcoholic euphoria, which nevertheless touched you. But I’m sure you’ve experienced the same, or at least could have. An intense emotional response to music is not hidden behind seven seals — the first recognition belongs to a young musician who wrote it while learning a piece by Bach.

And the second description was written by a woman who listened to Finnish tango in a pub.

It is striking that descriptions of musical experiences are often very similar. Sometimes so much so that expressions of emotions are not complete without clichés like «I was captured by the music» and so on. But clichés have developed because everyone experiences the same feelings. Although transcendental ecstasy as a reaction to music is seen in many cultures, the intense musical experience is not always blissful. Here is a listener’s recollection of Mahler’s Tenth Symphony:

«(There was) one chord so poignant and ominous that it caused sensations that have never been seen before … My brother felt the same: a primal, almost prehistoric horror seized us, we could not utter a word. We both looked at a black window and as if they could distinguish the face of Death from outside, which did not take its eyes off us.

From a cultural and psychological point of view, it seems incredible that it would occur to someone to write music that causes such states (one might argue that Mahler did not really set himself such a goal, but there are many examples, when musicians deliberately sought to upset their listeners and deprive them of their presence of mind). It is even stranger that it occurs to someone to experience the effect of such music (yes, some fall under its influence by accident, but many seek such an effect). Well, the strangest thing is that notes composed in a certain order can cause such a strong reaction. nine0009

It is even stranger that it occurs to someone to experience the effect of such music (yes, some fall under its influence by accident, but many seek such an effect). Well, the strangest thing is that notes composed in a certain order can cause such a strong reaction. nine0009

The question of how music fulfills this task is in the cultural and historical context, but the universal ability of music to influence a person lies outside the context. When Tolstoy wrote that «music is shorthand for feelings,» he expressed his approval and admiration for this feature, but in the fifth century Saint Augustine found the inevitable emotionality of music to be a very disturbing factor. He loved music, but he was weighed down by the thought that «parishioners are more enthusiastic about singing, and not about what they sing.» Medieval clerics ruefully admitted that music could incline to lust and lust, and not just call to piety; it was for these reasons that the counter-reformers sought to purify spiritual music from the corrupting secular influence. For the clergy, John Dryden’s remark had a downside: «What feelings can music not awaken or appease?» nine0009

For the clergy, John Dryden’s remark had a downside: «What feelings can music not awaken or appease?» nine0009

Why does music move us? Of all the questions about how our mind captures and processes music, this one will prove to be the most difficult. There is something unique and intangible in the magical effect of music. Many great paintings literally depict feelings in faces, in gestures or through circumstances, even abstract art can evoke associations through form and color: Yves Klein’s celestial, endless azure, Mark Rothko’s darkening horizons, scattered traces of Jackson Pollock’s insane intensity. Literature evokes emotion through narrative, characterization, and allusion, even if the «meaning» of a work can be flexible, the meaning is somehow kept within tight limits: for example, one would not say that «Great Expectations» is about the coal industry. But music is invisible and ephemeral: it sighs and roars, and the next moment it is gone. Except for occasional moments of deliberate mimicry, she is unlike anything else in this world. Certain phrases and tropes had a traditional «meaning» in the era of classicism; some believe that Western instrumental music has a set of meanings that can be objectively deciphered, but these assumptions are mostly built on shaky foundations — too simple, too superficial. In fact, it is incredibly difficult to explain why we can find shades of meaning in sound stimuli at all, much less start crying or laughing, dancing or going berserk over them. nine0009

Certain phrases and tropes had a traditional «meaning» in the era of classicism; some believe that Western instrumental music has a set of meanings that can be objectively deciphered, but these assumptions are mostly built on shaky foundations — too simple, too superficial. In fact, it is incredibly difficult to explain why we can find shades of meaning in sound stimuli at all, much less start crying or laughing, dancing or going berserk over them. nine0009

The issue of emotionality began to occupy cognitive psychologists and musicologists not so long ago. Eduard Hanslik wrote the book Vom Musikalisch-Schönen in 1854 (it was translated in 1891 under the title «Beauty in Music»). This work, the first serious contemporary study of musical aesthetics, emphasized that previously music had been discussed either «in dry and prosaic terms» of technical theory, or in aesthetic language «surrounded by a fog of extreme sentimentality». The author’s focus was not on emotionality as such, but on the aesthetic effect of the music, in particular the sense of beauty that arose when reason and feelings met. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Hanslick says, it was a matter of course that music was the creation of sound, aimed at transmitting and arousing passions. And yet he doubted the existence of a real analogy between a musical composition and the feelings it evokes. Beethoven was once considered a wild composer compared to Mozart’s cold clarity, and Mozart was once considered ardent compared to Haydn. “Certain feelings and emotions,” Hanslick argues, “cannot be found within the music itself.” nine0009

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Hanslick says, it was a matter of course that music was the creation of sound, aimed at transmitting and arousing passions. And yet he doubted the existence of a real analogy between a musical composition and the feelings it evokes. Beethoven was once considered a wild composer compared to Mozart’s cold clarity, and Mozart was once considered ardent compared to Haydn. “Certain feelings and emotions,” Hanslick argues, “cannot be found within the music itself.” nine0009

The question of whether music can convey specific emotions is rather complicated; I will return to its discussion later. But don’t doubt the ability of music to evoke some emotion in some people in some situations. Indeed, many would agree that the raison d’être of music is to evoke emotion. The question is how does she do it.

Gunslick insists that this mystery will forever remain unsolved. “The physiological process by which the perception of sound is transformed into feelings and into a state of mind is inexplicable, and so it is destined to remain,” he wrote. “Let’s not turn to science for explanations that it cannot give.” His opinion was overly pessimistic (and some will seem hopeful). Turning to the psychology of music with the intention of finding the «instrument» with which music inflames hearts ends in complete disappointment. At present, research on emotions seems highly inappropriate, even simple-minded. When neuroscientists figure out how and when subjects call pieces of music «happy» or «sad,» a music aficionado may perceive this experiment as a mockery of the emotive qualities of music — as if during a piano concerto, all we do is laugh or mope. nine0009

“Let’s not turn to science for explanations that it cannot give.” His opinion was overly pessimistic (and some will seem hopeful). Turning to the psychology of music with the intention of finding the «instrument» with which music inflames hearts ends in complete disappointment. At present, research on emotions seems highly inappropriate, even simple-minded. When neuroscientists figure out how and when subjects call pieces of music «happy» or «sad,» a music aficionado may perceive this experiment as a mockery of the emotive qualities of music — as if during a piano concerto, all we do is laugh or mope. nine0009

One way or another, the question of the emotionality of music formed the basis of the problems of musical cognition. Fortunately, in this regard, the atomistic dissection of music — and this approach has long been popular — has given way to observing how people react to listening to music: after all, hardly anyone experiences a storm of emotions from a monotonous sine wave produced by a tone generator; as a result, the «test material» of the researchers became more diverse.

2 compliant

2 compliant 0 delivers incredibly realistic gaming audio!

0 delivers incredibly realistic gaming audio! Please feel free to browse our website for other available items.

Please feel free to browse our website for other available items.

With the X-Fi Xtreme Fidelity 24-bit Crystalizer, MP3 music and movies are converted to Xtreme Fidelity, which delivers an experience beyond the original CD or DVD recordings.

With the X-Fi Xtreme Fidelity 24-bit Crystalizer, MP3 music and movies are converted to Xtreme Fidelity, which delivers an experience beyond the original CD or DVD recordings. 004%

004%